Effective Access Control for Asset Protection

- On 23/04/2025

Access Control for Asset Protection is a Vital Consideration For Security Managers

Effective Access Control for Asset Protection is a cornerstone of physical security (PHYSEC), essential for safeguarding critical assets including personnel, and supporting seamless operational service delivery.

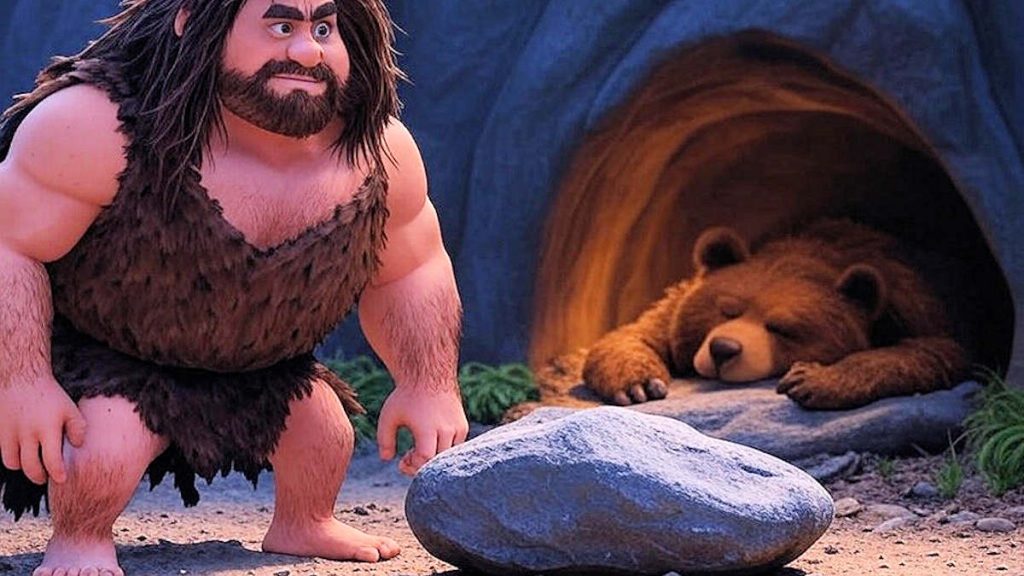

Referring to military defence in depth principles, this article outlines critical elements of access control, a concept tracing back to ancient times, when the first early human rolled a boulder to secure a cave entrance, while hoping not to disturb unwelcome carnivorous cave-dwelling company like hibernating bears.

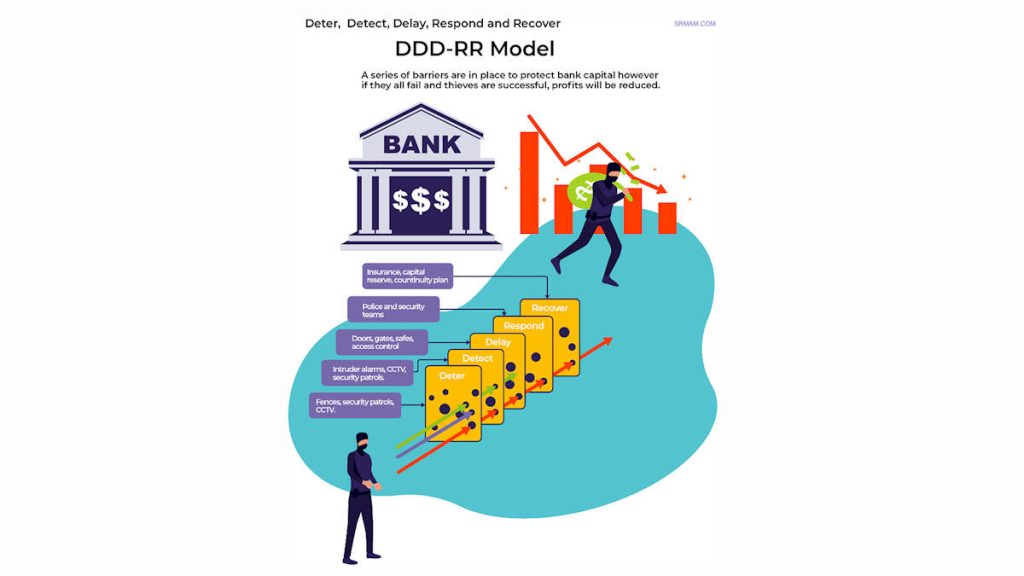

Image: Effective access control for asset protection 1 (Courtesy https://www.srmbok.com)

Access control systems are designed to deter, delay, deny, detect and respond to unauthorised intruders while not unduly impeding the movement and functions of legitimate known trusted individuals with a proven need to enter controlled areas.

Defining Access Control

Within the protective security context, access control includes physical barriers, electronic systems, procedural policies, monitoring, and response mechanisms to protect assets from unauthorised intrusion, compromise, theft, or damage.

Breaches in access control can damage the business mission and operations, with significant consequences, including:

- Workplace Violence: Incidents ranging from verbal harassment to criminal assault: security risk assessment (SRA) identifies high-value individuals who may be targets, such as senior executives or visiting VIPs.

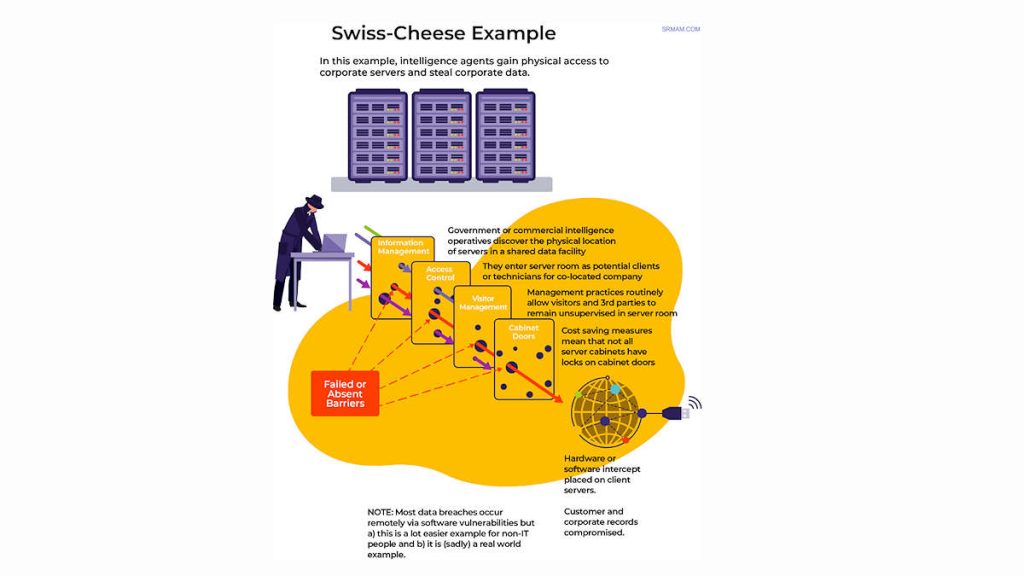

- Information Security Losses: Espionage, tampering, theft, or placement of technical surveillance devices targeting proprietary, sensitive, or classified information and system access credentials.

- Asset Loss or Damage: Theft, vandalism, or compromise of valuable equipment: SRA identifies mission-critical assets and specific protection requirements.

- Loss of Confidence: Diminished trust from government, clients, and the public in the organisation’s security effectiveness, potentially affecting budget funding and profitability.

- Operational Disruption: Undermining service delivery, up to and including physical attacks on facilities and resources.

Authentication

To enter controlled areas containing valuable and attractive assets, individuals must validate their legitimate need for access through authentication, using one or more of:

• Something You Have: A key, card, or token.

• Something You Know: A password or PIN.

• Something You Are: Biometric identifiers, such as facial recognition, fingerprints, voice, or iris scans.

Authentication devices are installed at the perimeter of sensitive areas, with additional controls to enter internal compartments for protected assets, such as vaults, armouries, classified information storage, ICT server rooms, and utilities.

Defence in Depth

Defence in depth is derived and developed from military engineering, employing multiple layers of protection to delay and mitigate an attack. Applied to access control, this approach enhances an organisation’s security posture by creating successive barriers, each with a distinct function, to reduce the likelihood of a successful breach.

The defence or security in depth principle is applicable to protecting both tangible assets (e.g., cash, equipment) and intangible assets (e.g., data). Tangible assets require robust physical barriers, such as vaults, to resist overt forcible attacks. In contrast, covert compromises of information, often by trusted insiders, are harder to detect and can have severe consequences, especially for classified national security data.

The diagrams below illustrate defence in depth considerations to protect tangible (cash at bank) and intangible (data) valuable assets, including using access controls.

Physical Security Barriers

Physical security barriers deter and delay unauthorised access. Examples include fences, walls, gates, doors and locks, each contributing to a comprehensive security framework.

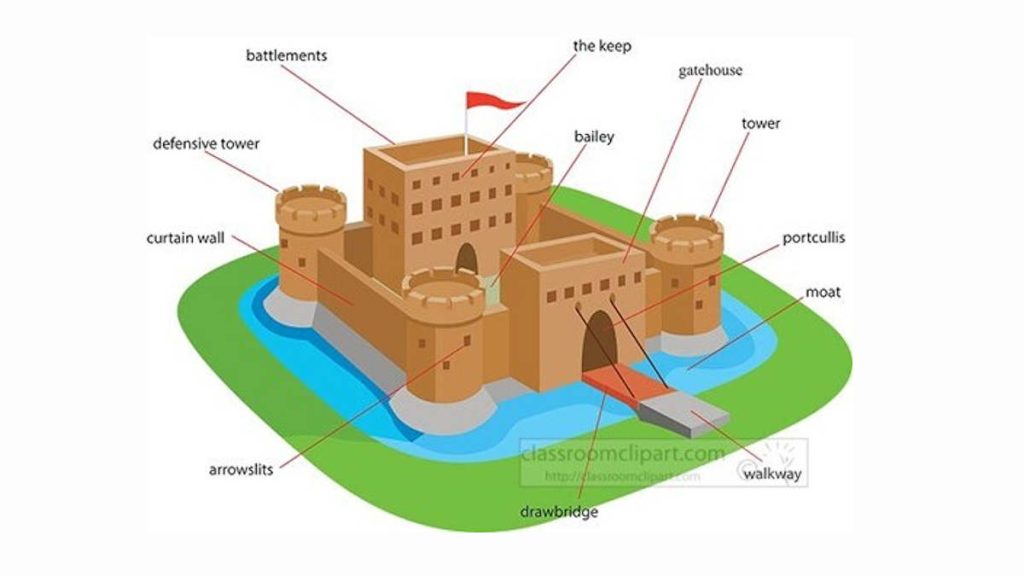

A point often overlooked is that castle designers were the first CPTED practitioners, even if they did not call their strategies CPTED, they incorporated many of its principles.

The concept of layered security dates to historical military fortification design, notably seen in medieval castles. Castles employed multiple defensive layers, including:

- Surrounding Terrain: Open fields providing visibility of approaching threats.

- Moat: A water barrier to impede advancement.

- Drawbridge and Portcullis: Controlled entry points to restrict access.

- Gatehouse and Walls: Fortified structures with defensive positions.

- Keep: The final stronghold for critical assets and personnel.

Image: Effective access control for asset protection 4 (Courtesy https://classroomclipart.com)

In modern contexts, access control systems must be installed in construction of comparable intrusion resistance. The “3D security zone cube” concept ensures that unauthorised access through floors, walls, ceilings, and roofs will produce permanent visible evidence of intrusion. Optimal materials include concrete, masonry, and brickwork, paired with solid-core timber doors in steel frames.

During business hours, electronic access control systems (e.g., cards, tokens, or PINs) with staff natural surveillance (eyesight) and awareness provides supervision of controlled areas.

After hours when controlled areas are unattended, non-latching deadlocking mechanical mortice locks are best practice, as electronic systems alone are vulnerable to defeat by determined adversaries with intent, capability and motivation. Facilities should enforce defined opening and lock-up routines, supported by staff training and continuous monitoring by the security response force.

Policies and Procedures for Access Control for Asset Protection

Robust policies and procedures define how access control measures are implemented, maintained, and enforced, covering:

• Access authorisation enrolment and removal

• Visitor management protocols

• Employee training and security awareness programs

• Incident response procedures

• Regular audits and reviews.

Comprehensive policies ensure consistent application and adaptability to evolving site asset protection risks and threats.

Response Force

Security personnel are critical to access control, serving as first responders to monitor access points, verify identities, and address incidents. Their presence deters potential intruders and provides a rapid response capability that technology, such as patrol drones or robots, cannot yet fully replicate.

Implementing Effective Access Control for Asset Protection

An effective access control strategy integrates physical barriers, electronic systems, procedural policies, and oversight by trusted personnel. Key steps include:

1. Conduct a Security Risk Assessment: Identify threats, vulnerabilities, and critical assets to determine necessary controls.

2. Design Layered Security: Implement a multi-layered approach with diverse barriers to achieve defence in depth.

3. Develop and Enforce Policies: Establish clear policies and ensure employee awareness and compliance.

4. Leverage Technology: Use integrated electronic security management systems for enhanced situational awareness, asset protection and data analysis.

5. Regularly Review and Update: Continuously monitor, audit, and refine measures to address emerging threats and business needs as an element of the SRA cycle.

Conclusion

Effective access control is vital for protecting corporate assets, personnel and operations. By adopting a defence-in-depth approach, organisations can create a resilient security framework that deters, detects, delays, and responds to unauthorised access attempts.

Implementing these PHYSEC principles, tailored to specific assets and risks, reduces the likelihood and consequences of incidents and breaches, safeguarding personnel, information, equipment, reputation, and service delivery capability.

Mark Jarratt is director and SCEC Security Zone consultant for Industry Risk. Board Certified in Security Management (Certified Protection Professional) in 1999, he has over 28 years of experience as a security manager and licensed consultant. He is a former vice-president of ASIS International Australia Region, chapter chairman, and certification instructor.